Eighteenth Century

When trying to understand what the Eighteenth century, it is essential to look back at this period of time without judging the behaviour of the time through the standards of today. Discrimination, slavery and racism were viewed in a totally different way during the 18th century when compared with today.

But to have any chance of understanding what went on within Francis Dashwood’s Brotherhood, we first need to understand what eighteenth century Britain was really like, its society, culture, morals and law.

But to have any chance of understanding what went on within Francis Dashwood’s Brotherhood, we first need to understand what eighteenth century Britain was really like, its society, culture, morals and law.

For the average person of the time the belief was that the law was there just to protect the landed gentry, with the poor and destitute having no rights at all.

The same could be said about Black people enslaved across the British Empire and the colonies, when inevitably brought back to Britain by their owners, they would still be treated as slaves after they arrived in England.

If they ran away from their owners, notices for runaway slaves would appear in all the criminals.

This continued until the case of James Somerset, a runaway slave who had been recaptured and held aboard a ship bound for Jamaica.

The slavery abolitionist, Granville Sharp, helped James Somerset to bring his case to court. As Sharp wanted to find out once and for all if slavery was legal in England.

On the 22 June 1772, judge Lord Mansfield recommended that the parties come to their own arrangement. But the parties insisted that the matter should be decided by the court. So, Lord Mansfield after long deliberation said” let justice be done whatever be the consequence”.

After much delay Lord Mansfield eventually gave a carefully worded judgement. He avoided the question of whether slavery was legal in England. Instead, he stated:

No master was ever allowed here to take a slave by force to be sold abroad because he deserted from his service, or for any other reason whatever.

After the verdict, James Somerset was freed.

Immediately afterwards the Somerset case was hailed by many as a victory. However, some slave owners ignored the ruling and continued to take Africans abroad forcibly.

The case of James Somerset was widely reported in the press and highlighted the question of slavery and British involvement in the slave trade.

The case became widely understood by the public as meaning that, ‘on English soil at least, no man was a slave’.

Unfortunately, even with public opinion supporting the abolition of slavery it wasn’t until the Slave Trade Act in 1807 that the slave trade was abolished in England and in 1833, with the Slavery Abolition Act, slavery itself was formally abolished.

The same could be said about Black people enslaved across the British Empire and the colonies, when inevitably brought back to Britain by their owners, they would still be treated as slaves after they arrived in England.

If they ran away from their owners, notices for runaway slaves would appear in all the criminals.

This continued until the case of James Somerset, a runaway slave who had been recaptured and held aboard a ship bound for Jamaica.

The slavery abolitionist, Granville Sharp, helped James Somerset to bring his case to court. As Sharp wanted to find out once and for all if slavery was legal in England.

On the 22 June 1772, judge Lord Mansfield recommended that the parties come to their own arrangement. But the parties insisted that the matter should be decided by the court. So, Lord Mansfield after long deliberation said” let justice be done whatever be the consequence”.

After much delay Lord Mansfield eventually gave a carefully worded judgement. He avoided the question of whether slavery was legal in England. Instead, he stated:

No master was ever allowed here to take a slave by force to be sold abroad because he deserted from his service, or for any other reason whatever.

After the verdict, James Somerset was freed.

Immediately afterwards the Somerset case was hailed by many as a victory. However, some slave owners ignored the ruling and continued to take Africans abroad forcibly.

The case of James Somerset was widely reported in the press and highlighted the question of slavery and British involvement in the slave trade.

The case became widely understood by the public as meaning that, ‘on English soil at least, no man was a slave’.

Unfortunately, even with public opinion supporting the abolition of slavery it wasn’t until the Slave Trade Act in 1807 that the slave trade was abolished in England and in 1833, with the Slavery Abolition Act, slavery itself was formally abolished.

Society at this time accepted slavery as the norm, along with the poor and destitute being jailed just for being poor.

During this period more than 200 offences were regarded as serious enough to be punishable by death. Serious offenders who were not hanged were transported to the colonies, an alternative form of punishment introduced by an Act of Parliament in 1718.

There was nevertheless a large prison population, there were those awaiting trial for non-custodial punishment. Those actually sentenced to a term of imprisonment, and those who had not discharged their debts.

Debtors were by far the largest element in the 18th century prison population, often innocent tradespeople who had just fallen on hard times.

During this period more than 200 offences were regarded as serious enough to be punishable by death. Serious offenders who were not hanged were transported to the colonies, an alternative form of punishment introduced by an Act of Parliament in 1718.

There was nevertheless a large prison population, there were those awaiting trial for non-custodial punishment. Those actually sentenced to a term of imprisonment, and those who had not discharged their debts.

Debtors were by far the largest element in the 18th century prison population, often innocent tradespeople who had just fallen on hard times.

With legal action being taken against them by creditors, kept them in prison until they paid their debts.

The overcrowding of local prisons with debtors was dealt with every few years by Parliament which would pass an insolvency Act to discharge them on certain conditions. There were 32 such Acts between 1700 and 1800.

Prisons ranged from small village lock-ups in rural areas, to the cellars of castles in towns. The largest prisons were in the cities like London, the most important being Newgate with around 300 prisoners.

The overcrowding of local prisons with debtors was dealt with every few years by Parliament which would pass an insolvency Act to discharge them on certain conditions. There were 32 such Acts between 1700 and 1800.

Prisons ranged from small village lock-ups in rural areas, to the cellars of castles in towns. The largest prisons were in the cities like London, the most important being Newgate with around 300 prisoners.

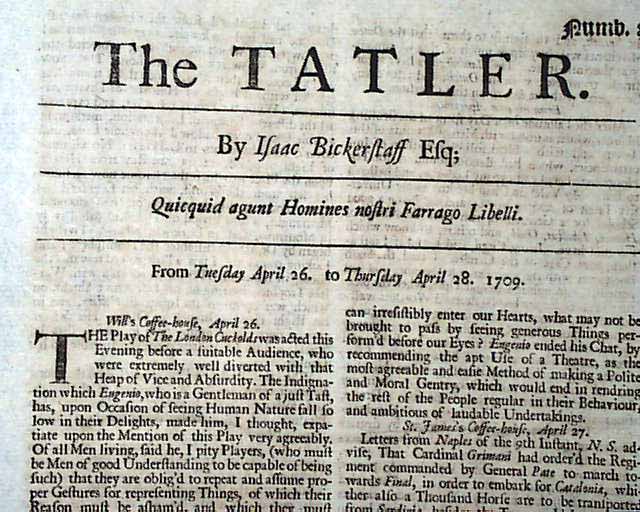

When it came to the media nothing changed over the centuries, just like today the newspapers or scandal sheets of the time as they were known, would feed the reading public's insatiable appetite for gossip.

To catch up on the latest gossip men would go to the coffee houses and gentlemen’s clubs, whilst the ladies would meet up at the India tea houses to read the latest gossip from the social media of the time, such as The Tatler, The Flying Post, The British Apollo, The Spectator, The Observator or the Female Tatler.

Almost all of these scandal sheets claimed that their purpose was to be instructional and morally edifying.

The scandal sheets quite frequently suggested that it was the public Taverns, coffee and gin houses with their excessive drinking and general behaviour were the cause of the moral decline in Britain, with one paper quoting those men and woman with their promiscuous behaviour and rolling around roaring drunk in the streets of Britain were dragging society quite literally into the gutter.

The influence of the scandal sheets swayed public opinion, which was growing stronger against both the leading political parties of the time. With the liberal Whigs and the Tories being constantly bullied and ridiculed in print and with most politicians and clergy being satirised mercilessly with stories and illustrations of misbehaving priests, monks and nuns.

In a way it was inevitable that with all the gossip generated by the tabloid press, that gentlemen would require a place to conduct discrete business and enjoy their spare time away from the glare of the scandal sheets.

The influence of the scandal sheets swayed public opinion, which was growing stronger against both the leading political parties of the time. With the liberal Whigs and the Tories being constantly bullied and ridiculed in print and with most politicians and clergy being satirised mercilessly with stories and illustrations of misbehaving priests, monks and nuns.

In a way it was inevitable that with all the gossip generated by the tabloid press, that gentlemen would require a place to conduct discrete business and enjoy their spare time away from the glare of the scandal sheets.

London became the clubbers haven by the 1750s, with up to twenty thousand men assembling most nights at one of the many clubs that had been formed. Clubs like the famous Brook’s, Boodle’s and Whites clubs still around today, many of the clubs were just social gatherings or dining clubs, like Hoydens, the Calves Head Club and the Sublime Society of Beefsteaks.

There were also the debating societies like the Robin Hood society and the Athenian Society, while other societies had a more artistic outlook such as the Society of Antiquaries of London and the Society of the Dilettanti.

In 1736 the society of the Dilettanti had 46 members including Francis Dashwood one of the founding members of the society, members were mostly young men of rank and fashion with new members having to be personally known to an existing member and elected in a secret ballot.

The name Dilettanti comes from the Latin 'dilettare', to take delight in, and the Society adopted a policy of “seria ludo” which translated means “Delight in serious Play.

There were of course the political societies like the Kit-Kat Club which met at the Cat and Fiddle Tavern in Gray’s Inn Lane in the West End of London, which was literary and gallant and was the political stronghold of the Whigs political party.

By the mid 1750’s Gentlemen’s clubs were becoming powerful, influential and political, so when Joseph Addison the founder of The Spectator magazine was approached to become a member of the Kit-Kat club, its primary aim was to be able to sensor what went to print and effectively cover up the antics of the club and alleviate any bad press.

The Diabolical Academy was a weekly dancing club or Buttock Ball as it was more commonly known, with membership made up of mainly of Bullies, Libertines and Strumpets. The dancing would take place on Thursday evenings at an undisclosed tavern, where attendees were ‘Welcome in Masquerade’ guests were not only just able to dance but were also able to use one of the Resting-Rooms’ in which couples could ‘whisper away the night’.

Although in general most clubs were in the main for gentlemen only, the ladies of the day had their own outlets for entertainment thus Duchess of Newcastle drew up her own guide to “what’s on in London”, she listed not merely theatres, pleasure gardens, she also included the clubs of the working women, where they would meet after selling their wares each day, where the women would heartily indulge in warm ale and brandy.

A popular leaflet was published around the 1760’s “The New Art and Mystery of Gossiping”, which described the ‘Women’s Club’s in and around the City and Suburbs of London.

The leaflet provides derisory descriptions of the gossipy nature of female clubs and bemoans the fact that ‘those Clubs have become so common among the Fairer Sex’.

The list of clubs given by the author is particularly striking, the names of the clubs, such as “The Fish Women’s Club” at Billingsgate, the “Basket Women’s Club” in St Giles and the “Taylor’s Wives Club” in Monmouth Street, are extremely redolent of the forms of female alehouse clubs which were based on the vocational trade of the women.

There were also the debating societies like the Robin Hood society and the Athenian Society, while other societies had a more artistic outlook such as the Society of Antiquaries of London and the Society of the Dilettanti.

In 1736 the society of the Dilettanti had 46 members including Francis Dashwood one of the founding members of the society, members were mostly young men of rank and fashion with new members having to be personally known to an existing member and elected in a secret ballot.

The name Dilettanti comes from the Latin 'dilettare', to take delight in, and the Society adopted a policy of “seria ludo” which translated means “Delight in serious Play.

There were of course the political societies like the Kit-Kat Club which met at the Cat and Fiddle Tavern in Gray’s Inn Lane in the West End of London, which was literary and gallant and was the political stronghold of the Whigs political party.

By the mid 1750’s Gentlemen’s clubs were becoming powerful, influential and political, so when Joseph Addison the founder of The Spectator magazine was approached to become a member of the Kit-Kat club, its primary aim was to be able to sensor what went to print and effectively cover up the antics of the club and alleviate any bad press.

The Diabolical Academy was a weekly dancing club or Buttock Ball as it was more commonly known, with membership made up of mainly of Bullies, Libertines and Strumpets. The dancing would take place on Thursday evenings at an undisclosed tavern, where attendees were ‘Welcome in Masquerade’ guests were not only just able to dance but were also able to use one of the Resting-Rooms’ in which couples could ‘whisper away the night’.

Although in general most clubs were in the main for gentlemen only, the ladies of the day had their own outlets for entertainment thus Duchess of Newcastle drew up her own guide to “what’s on in London”, she listed not merely theatres, pleasure gardens, she also included the clubs of the working women, where they would meet after selling their wares each day, where the women would heartily indulge in warm ale and brandy.

A popular leaflet was published around the 1760’s “The New Art and Mystery of Gossiping”, which described the ‘Women’s Club’s in and around the City and Suburbs of London.

The leaflet provides derisory descriptions of the gossipy nature of female clubs and bemoans the fact that ‘those Clubs have become so common among the Fairer Sex’.

The list of clubs given by the author is particularly striking, the names of the clubs, such as “The Fish Women’s Club” at Billingsgate, the “Basket Women’s Club” in St Giles and the “Taylor’s Wives Club” in Monmouth Street, are extremely redolent of the forms of female alehouse clubs which were based on the vocational trade of the women.

With the ladies and gentlemen of society catered for, it was the local Taverns that were the haunting grounds of the workers.

The workers taverns were not simply the haunt of drunken groups of working men and women drinking in the bar, ladies of respectable repute often accompanied their husbands to drinking establishments and taverns, where they could enjoy the company of each other in smaller discrete rooms.

As well as the mainstream clubs there were a number of secret societies, a group of which were known as the Molly House’s. These were a cross between what today we would call a gay club and brothel, with the most infamous of which being owned by Margaret Clap of Field Lane in Holborn.

Male homosexuality effeminacy and so-called sexual deviancy was commonly practiced at this time, with many of the overdressed men of fashion by their dress code implying that they were effeminate and lacking in heterosexual masculine prowess.

Painter William Hogarth produced a “Taste in High Life” in 1746 which focuses on the figure of a fashionable, effeminate gentleman which demonstrates his homosexuality without ever directly referencing it.

There are many recorded men of society during this time such as courtier John Hervey who was openly bisexual and effeminate, and is believed to have had indiscreet affairs with the Earl of Ilchester and Frederick, Prince of Wales.

There were several notorious locations around London for effeminate, men, such as a lane in Moorfields known as Sodomite's Walk on the south side of Finsbury Square. But frequently frequenting these areas along with the houses could be dangerous places to be associated with, as homosexual acts between men were punishable by being pilloried, penal service or even death.

The perception is that effeminate men were from the socially elite, but when we look at the accounts of police raids on London molly houses and street locations that effeminate men frequented, the men arrested were from a variety of social backgrounds including tradesmen, artisans and apprentices.

William Brown was pilloried and sent to prison in 1726 after being arrested in Sodomite's Walk by an agent provocateur. He was proudly unrepentant when charged by the police with 'attempted sodomy’ and stated in his defence "I think there is no crime in making what use I please of my own body."

But Molly houses were not just the meeting places for Gay men, women who loved women would often meet up in similar societies and were equally prey to gossip. The successful sculptor Anne Damer cousin of Horace Walpole suffered a numerous public and private attacks on her as a lesbian. It was during travels on the continent to study art, in the years immediately after being widowed those rumours began to circulate that Anne Damer was a lover of women.

The rumours were spread by a number of satirical publications that mentioned her using pseudonyms in such ill-disguised form that there was no question who was intended. In addition to being referred to as a “Sapphick”, she was called a “Tommy” in a very early example of this slang term being used for a lesbian. There was no solid evidence that she was sexually active with women, but even in the face of powerful friends taking publishers to task for printing the satires and verses, the rumours continued for two decades before gradually fading.

In Tottenham Court Road during the 1720s a particular molly house was run by Julius Caesar Taylor, a free black man. Initiation rituals for visitors included being given a female name and having a glass of gin thrown in their faces. Taylor was arrested and found guilty in 1728 of having indecent relations with another man. He was also found guilty of "keeping a disorderly House and entertaining wicked abandoned Men, who commited sodomitical Practices". Other molly houses included Plump Nelly's in Giltspur Street, run by Samuel Roper otherwise known as Plump Nelly and his wife. Plump Nelly was arrested in 1725 at the Hart Street molly house. In 1726 he was arrested again for sodomy and for keeping a disorderly house. He died in the Poultry Compter a local prison in Cheapside London while awaiting trial.

There were several notorious locations around London for effeminate, men, such as a lane in Moorfields known as Sodomite's Walk on the south side of Finsbury Square. But frequently frequenting these areas along with the houses could be dangerous places to be associated with, as homosexual acts between men were punishable by being pilloried, penal service or even death.

The perception is that effeminate men were from the socially elite, but when we look at the accounts of police raids on London molly houses and street locations that effeminate men frequented, the men arrested were from a variety of social backgrounds including tradesmen, artisans and apprentices.

William Brown was pilloried and sent to prison in 1726 after being arrested in Sodomite's Walk by an agent provocateur. He was proudly unrepentant when charged by the police with 'attempted sodomy’ and stated in his defence "I think there is no crime in making what use I please of my own body."

But Molly houses were not just the meeting places for Gay men, women who loved women would often meet up in similar societies and were equally prey to gossip. The successful sculptor Anne Damer cousin of Horace Walpole suffered a numerous public and private attacks on her as a lesbian. It was during travels on the continent to study art, in the years immediately after being widowed those rumours began to circulate that Anne Damer was a lover of women.

The rumours were spread by a number of satirical publications that mentioned her using pseudonyms in such ill-disguised form that there was no question who was intended. In addition to being referred to as a “Sapphick”, she was called a “Tommy” in a very early example of this slang term being used for a lesbian. There was no solid evidence that she was sexually active with women, but even in the face of powerful friends taking publishers to task for printing the satires and verses, the rumours continued for two decades before gradually fading.

In Tottenham Court Road during the 1720s a particular molly house was run by Julius Caesar Taylor, a free black man. Initiation rituals for visitors included being given a female name and having a glass of gin thrown in their faces. Taylor was arrested and found guilty in 1728 of having indecent relations with another man. He was also found guilty of "keeping a disorderly House and entertaining wicked abandoned Men, who commited sodomitical Practices". Other molly houses included Plump Nelly's in Giltspur Street, run by Samuel Roper otherwise known as Plump Nelly and his wife. Plump Nelly was arrested in 1725 at the Hart Street molly house. In 1726 he was arrested again for sodomy and for keeping a disorderly house. He died in the Poultry Compter a local prison in Cheapside London while awaiting trial.